Note: This compilation was done as a Women's Studies project

at the University of Maine, Orono, and submitted on December 15, 1997

The Making of a Family Heirloom

By Jean Hay

Some families have real heirlooms -- notable pieces of furniture, jewelry or silverware handed down from generation to generation, with the name and relationship of the appropriate ancestor attached. Sometimes, but not always, family stories come with the pieces.

One of the distinguishing features of those kinds of heirlooms has been that their inherent value, apart from the family history, was recognized by the real world, as could be seen by the auction prices when such pieces occasionally wound up at a prestigious public sale.

In recent years the value of many of those family heirlooms has been enhanced by their attachment to those family histories. Notable items become even more valuable when they were once owned by the likes of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis or Princess Diana.

Ours is not a family like those. Our possessions do not have much inherent value. In fact, many of our most prized ones were once someone else's throwaways. But what those prized pieces do come with are family stories.

It is those stories that make what passes for heirlooms valuable for families like ours.

What follows is a recounting, with photos, of some of my family's heirlooms.

Old Oaken Desk

This desk was once owned by the Providence Journal-Evening Bulletin. It was gracing its South County office in Wakefield, Rhode Island when I was hired on as an editorial assistant in 1970.

I was a little hesitant in my new job. In my employment interview, when I tentatively asked just what an editorial assistant did, Westerly bureau chief Norm Warner said he didn't have a clue. The main office had ordered its two southern-most news bureaus to be consolidated, and authorized the new position for which I was applying. He assured me that he would think of something, and hired me on the spot.

I was a little hesitant in my new job. In my employment interview, when I tentatively asked just what an editorial assistant did, Westerly bureau chief Norm Warner said he didn't have a clue. The main office had ordered its two southern-most news bureaus to be consolidated, and authorized the new position for which I was applying. He assured me that he would think of something, and hired me on the spot.

With the consolidation came the option of new office furniture. Warner, with his crew cut, misshapen long trench coat and brusque style, was an old-time rough and tumble journalist who cared naught for style -- outside his news stories. If that's what the main office wanted him to work on – new, tinny metal, military-green desks with smooth, asphalt-like tops — that was just fine with him. He quickly ordered the old, bulky, five-foot-wide, also dark, military-green, wooden desks to the trash heap.

At the time I was the young military wife of a Navy Seabee who had spent two tours of duty in Vietnam and who would be discharged later that same year from the Navy base at Davisville. We were a struggling young couple with little furniture, and not a desk to our names. I asked about the possibility of diverting one of the wooden monstrosities off of the trash truck and into a quaint little rented bungalow just up the road.

And thus it came to pass that we became the owners of a well-built, heavy, ugly green-colored, oaken desk once owned by the Providence Journal.

I immediately put the paint stripper to it, and discovered the solid oak underneath. The top has an oak veneer which, evidence shows, yielded a bit under my too-enthusiastic sanding.

So far the desk has survived several moves and has proved more durable than two long-term relationships, including the one in effect at the time of its acquisition.

So far the desk has survived several moves and has proved more durable than two long-term relationships, including the one in effect at the time of its acquisition.

Just a word about the Olympia manual typewriter pictured on the desk. Although a manual typewriter does portray the latest in journalistic technology at the time the desk was acquired, that is not the only thing this particular typewriter represents.

The typewriter was among the cast-offs of the Bangor Daily News, which were offered to employees for $10 each when the company computerized. Dave Bright, who then worked for the BDN, donated the typewriter to my 1994 congressional campaign, at a time when I and the rest of the world presumed that Republican Congressman Olympia Snowe would be running for re-election -- and I was running hard against her.

Notice that the trademark on the typewriter has been altered with a red circle and slash mark through the word ``Olympia.'' Not only was that typewriter inspirational to the campaign troops, but it was used as a prop in one of the funky television commercials we did for the campaign.

Olympia, of course, jumped ship on me, running instead for the U.S. Senate seat in Maine when Sen. George Mitchell decided to retire, which he did a mere three weeks before the filing deadline for candidates to get on the ballot. Several Democrats then jumped into the congressional race, and I lost the Democratic primary to John Baldacci, who went on to win the congressional seat.

Also on the desk is an aloe vera plant that refuses to die, despite years of neglect in a pot too small for its bulk.

The chair at the desk is an $8 special found at a junk shop with one arm broken off. It is a work in process (I've only had it about 15 years -- or so), with a new left arm hand-carved and ready to glue into place as soon as I get around to replacing the torn chair seat with new caning.

The cat, named Lilly, is also a cast-off, rescued from the local pound after I heard rodent scratchings inside the walls of my newly acquired, uninsulated, 100-year-old house in Bangor in early 1996. A week later I found a dead and masticated rat in the middle of the dining room rug. Since then, Lilly has done a fine job keeping the bats out of the attic, although I wish she wouldn't jump on the bed with them in the middle of the night.

The cat, named Lilly, is also a cast-off, rescued from the local pound after I heard rodent scratchings inside the walls of my newly acquired, uninsulated, 100-year-old house in Bangor in early 1996. A week later I found a dead and masticated rat in the middle of the dining room rug. Since then, Lilly has done a fine job keeping the bats out of the attic, although I wish she wouldn't jump on the bed with them in the middle of the night.

Peasant Gourmet sign

This sign, measuring a little more than 2-by-5, hung over a shop I opened in 1978 in Blue Hill, Maine. The sign is a single piece of wood, about three inches thick, which was specially-milled from a huge pine tree cut down by my then-father-in-law, Keith R. Heavrin, Sr., on his property in Sedgwick, Maine. I hand-carved the lettering into the slab, and stained the letters dark before finishing the entire piece with several coats of clear urethane.

Two other large slabs were sistered and made into a large dining room table by Keith R. Heavrin, Jr. It remains with him at his home in Harborside, Maine. A third, smaller slab from farther up the tree, is now a coffee table owned by our daughter Rebecca Heavrin.

Two other large slabs were sistered and made into a large dining room table by Keith R. Heavrin, Jr. It remains with him at his home in Harborside, Maine. A third, smaller slab from farther up the tree, is now a coffee table owned by our daughter Rebecca Heavrin.

The shop's name was based on the principle that peasants, who by definition have the closest possible personal relationship to their food, are the ones who really know how to eat well. The original motivation was to provide a retail outlet for our home garden, some 22 miles away, as well as to fill a niche in the area for good, solid, home-made or home-grown food, at a time when the produce sold in Blue Hill was pitiful, over-priced and tasteless. The perfect location for the Peasant Gourmet Shop was found in the form of a newly vacated blacksmith shop in the middle of the Village of Blue Hill,

The shop sold home-baked bread and baklava (bought in locally), home-made jams (by moi), herbal and specialty teas, organic coffee, dozens of different kinds of herbs and spices available nowhere else in town, and fresh fruit and produce, from our home garden, from area farmers, and, as a last resort, from the Boston market.

I arranged to get same-day service from the wholesale produce depot in Chelsea, Mass., by having my order back-hauled in a refrigerated seafood truck that had left the fishing village of Stonington early that morning. I made this arrangement after I realized those trucks were dropping off their loads at the wholesale fish market just a few miles away from the Chelsea market, and would normally return empty, driving right past my shop in Blue Hill on their way back to Stonington.

This three-part plan guaranteed that my shop had the freshest produce to be found anywhere in town, along with the freshest bread and other goodies. The well-heeled population of Blue Hill, although a bit puzzled by the name of the establishment, responded enthusiastically.

But, ah, it was not to be. Although the idea was good, the motivation died.

The shop opened in May of 1978. On July 9, 1978, my husband informed me that he had been having a long-term affair with a young woman we had brought into our home as a farm apprentice a few years before, and that he didn't want to be living a double life anymore.

We were divorced the following January. I got a job as a reporter at the Bangor Daily News, sold off the equipment in the shop, and took down the sign. The shop reopened as the Blue Hill Gourmet, and lasted several years until the adjacent gourmet restaurant, the Firepond, merged with it and moved into that space.

The Chest of Drawers

The job at the Bangor Daily News was based in the Hancock County bureau in Ellsworth. The steady paycheck enabled me to go house hunting, which landed me at the old Carter homestead on Route 172 in Blue Hill. The roughly 10-acre parcel of land, old farmhouse, and rickety barn in the process of falling down, was situated about a mile from my old haunt at the Peasant Gourmet. It was also about the same distance from both the town's public elementary school and the semi-private George Stevens Academy, which serves as the area's regional high school.

The house was then owned by Evelyn Carter Candage, the elderly widow of a fisherman, and was badly in need of repair -- which, of course, was why I could afford it. It had no bathroom, only a toilet in a windowless closet with no sink -- a situation which was one toilet more than in my former owner-built, non-electric home in Harborside. Without insulation of any kind, the old two-story farmhouse had no central heating, using instead a woodstove

and a smelly oil burner in what passed for the living room. We had heated solely with wood in our homesteading cabin on our 22 acres in Harborside. I was undeterred. The first few winters were unbelievably cold. The house got more comfortable over the years as I pulled down old plaster walls and insulated between the post and beams and full-dimension studs.

and a smelly oil burner in what passed for the living room. We had heated solely with wood in our homesteading cabin on our 22 acres in Harborside. I was undeterred. The first few winters were unbelievably cold. The house got more comfortable over the years as I pulled down old plaster walls and insulated between the post and beams and full-dimension studs.

The electrical wires in the farmhouse, mostly BX cable, seemed to be the same vintage as Thomas Edison himself. With four bedrooms, the house had a full attic that could only be accessed through a three-foot-square hole in the ceiling of what was then the upstairs sewing room, but which I soon converted into a full bath.

In the haymow of the barn, which was already tilting recklessly toward the road a few feet away, were some cast-off pieces of furniture, including some rusty metal bedframes and a few pieces of bedroom furniture. We emptied out everything that looked usable to make room for the hay we needed for the ponies I got for the kids (partly to fulfill one of my own childhood fantasies and partly to feel less guilty for having gotten divorced). When the kids outgrew the ponies, I had the barn demolished.

One of the pieces of furniture that had been relegated to the haymow is pictured here. It had belonged to the widow's son when he was a boy, and ripped children's stickers and smiley faces dotted its scratched and dirty, dark, cracked-varnish finish. Desperately in need of furniture, I appropriated the piece for my own use, cleaned it up a bit, and promised to do a proper finishing job on it when I got the time.

It was 16 years and another move later before I got the time. I refinished this piece in 1996, resurrecting a lovely cherry highboy hiding under all that crap.

The small lamp pictured on the highboy is a dump find, one of two identical touch-lamps which had been discarded at the Blue Hill transfer station when one of the rheostats that controls the touch-lamp switch had burned up. Suspecting that to be the case, I took them home, by-passed the wiring to the rheostats, and gained two nice bedside lamps.

The Table

During the 1970s, in the coastal town of Sedgwick, a few hundred yards inland from the shores of Eggemoggin Reach, was a whimsical restaurant known as Wind in the Willows. It was a funky meeting place, with sporadic, odd, live music and an eclectic menu. Run on a shoestring and a prayer, it went belly-up after a few years. The owner left town. And so it sat for several years, the buildings looking more and more down-at-the-mouth with ever passing year.

Shortly after I had bought my farm in Blue Hill, I heard that the property had been sold, and that the new owner was in town. In my capacity as a reporter, unable to locate a phone number for the new owner, I went down to Sedgwick to see if I could ambush a story.

I did get a story. The new owner and his wife were going to open a gift shop.

As he was explaining this to me, a pick-up truck was backing up to a graying old square-grand piano, which had been used to entertain the guests in the outdoor, screened-in pavilion adjacent to the restaurant. The piano had been under the pavilion roof, but out in the weather with only screens for protection, for more than three years.

` `What are you going to do with that?'' I asked.

``Take it to the dump,'' he replied. ``It's not any good any more.''

``Gee, I know some people who restore pianos,'' I said excitedly. ``Can I talk you into trucking that to my house in Blue Hill?''

``Gee, I know some people who restore pianos,'' I said excitedly. ``Can I talk you into trucking that to my house in Blue Hill?''

``Too far,'' he said simply.

``What if I find another way to get it there?''

``Young lady,'' he said, ``we're going to clear this place out today. We'll save that thing for last, but if we're ready to go and you're not back, it'll be gone.''

``Fair enough,'' I said, and I was off to hijack a friend's truck -- along with a burly friend or two, since that piano must have weighed close to a quarter-ton.

Once it was safely in my living room, I called in my restorative friends to inspect my prize. They gave me a verdict I did not want to hear. It would cost about $3,000 -- money I did not have -- to restore it to new, they said, and even if it were restored to new, I would not have much of a piano, since square grands were never a good design for a piano and weren’t around long for that reason.

Bummer.

I looked at the piano again, at the slightly-battered, mostly-intact, hand-carved lion-head legs, at the curling mahogany veneer on the piano itself, at the filigree carvings and trim all around.

I was still in love.

I looked at my sparsely furnished home. And I decided I needed a table.

Off came the folding lid. A few bolts and huge screws, and out came the keys (made with real ivory) and the hammers. Then, with great difficulty, the 200-pound solid iron sounding board and strings, looking much like a very heavy harp, were extracted. A sizable crowbar helped break the bond of an incredibly strong 100-year-old horse glue holding the foot-high sides of the frame to the three-inch-thick solid oak base.

Voila, I had a place to eat dinner.

It was only years later that I realized my hard-won dining room table was about the same size, shape, and thickness as the one my ex-husband had made out of those two slabs from his father's old pine.

Only mine was fancier.

Old Goat Soap

After six years as a reporter and bureau chief for the Bangor Daily News, I paid off the mortgage on my farm. By that time I had hooked up with an organic farmer who, with his brother, had a farm off the beaten track. With my farm's roadside location a mile from the middle of Blue Hill Village, we decided to go into business together, with a retail farmstand on my property. I figured it would be good for the kids to have a farm in their back yard, and I wasn't seeing enough of them with all the night meetings I had to attend as a reporter. I quit my job with the Bangor Daily News in July 1985.

For the next seven years I grew vegetables, strawberries, raspberries, herbs and flowers. My partner Dennis grew the bigger stuff that could be tended from a tractor, such things as corn, squash, potatoes, rows and rows of carrots.

For the next seven years I grew vegetables, strawberries, raspberries, herbs and flowers. My partner Dennis grew the bigger stuff that could be tended from a tractor, such things as corn, squash, potatoes, rows and rows of carrots.

Dennis and his brother also owned a flock of sheep, with about 50 ewes, plus a few goats thrown in to eat the brush in the pasture that the sheep disdained. Every spring brought the lambing, and every fall the ``harvest'' of 60 to 80 lambs and a few old ewes, most of the meat pre-sold for home use.

One thing most people did not choose to take with their frozen cuts of meat was the fat trimmings. I did not like to see the fat thrown out, but, unlike pork fat which could be rendered into usable lard, sheep and goat fat was not good for much of anything.

Except, that is, for making soap.

Dennis bought me a simple how-to book on soapmaking, and I was off and running. I learned how to make decent, plain, ordinary, old-fashioned lye soap, with only a few bad batches that simply refused to harden.

I got good at it, but after making all the soap the family would need in a year, we still had fat left over. I decided to make it to sell in the farmstand.

I needed a name for this ordinary, round peasant soap, like grandma used to make, only better.

Long disgusted with the advertising hype on so many products, I decided to call this very plain but useful product by the worse name I could think of, dress it up in the fanciest packing I could devise, and see what happened.

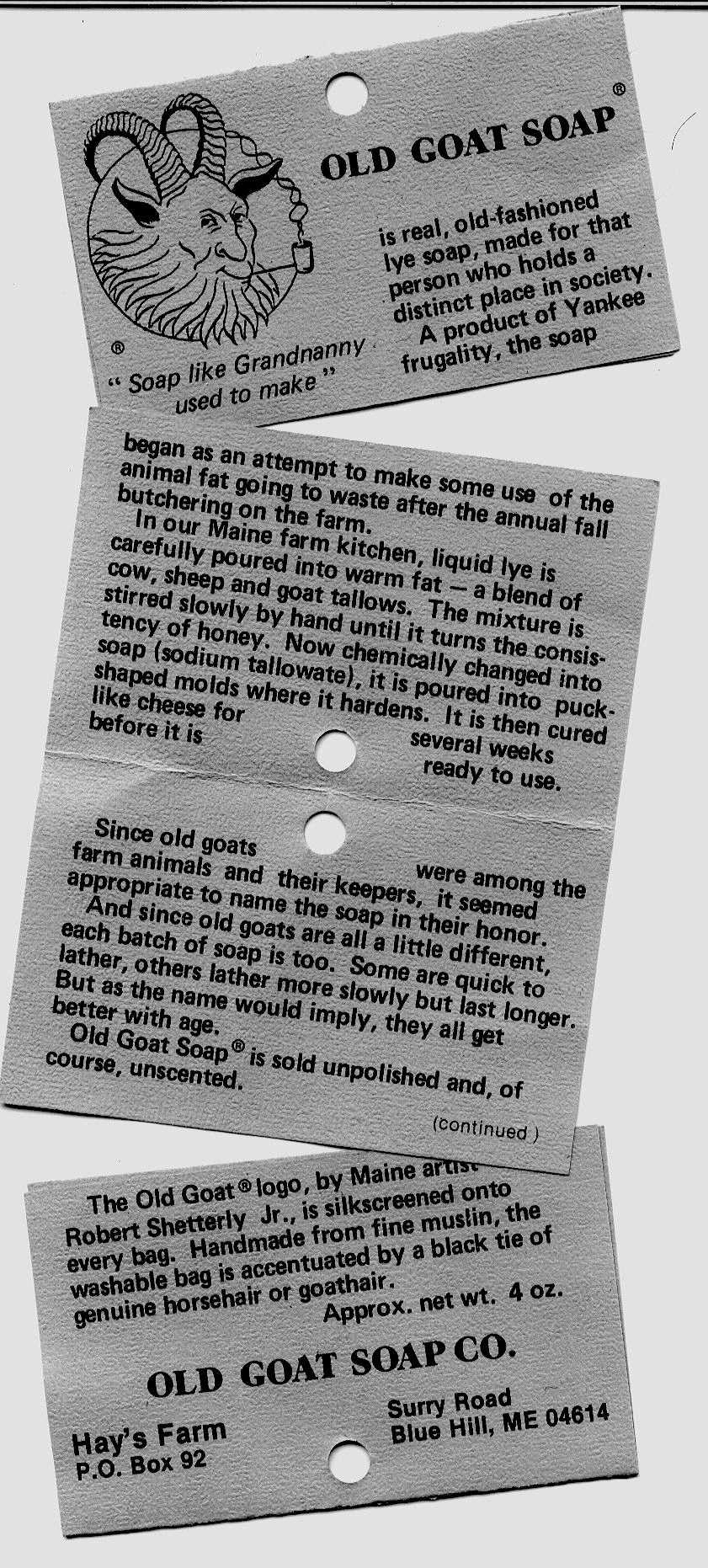

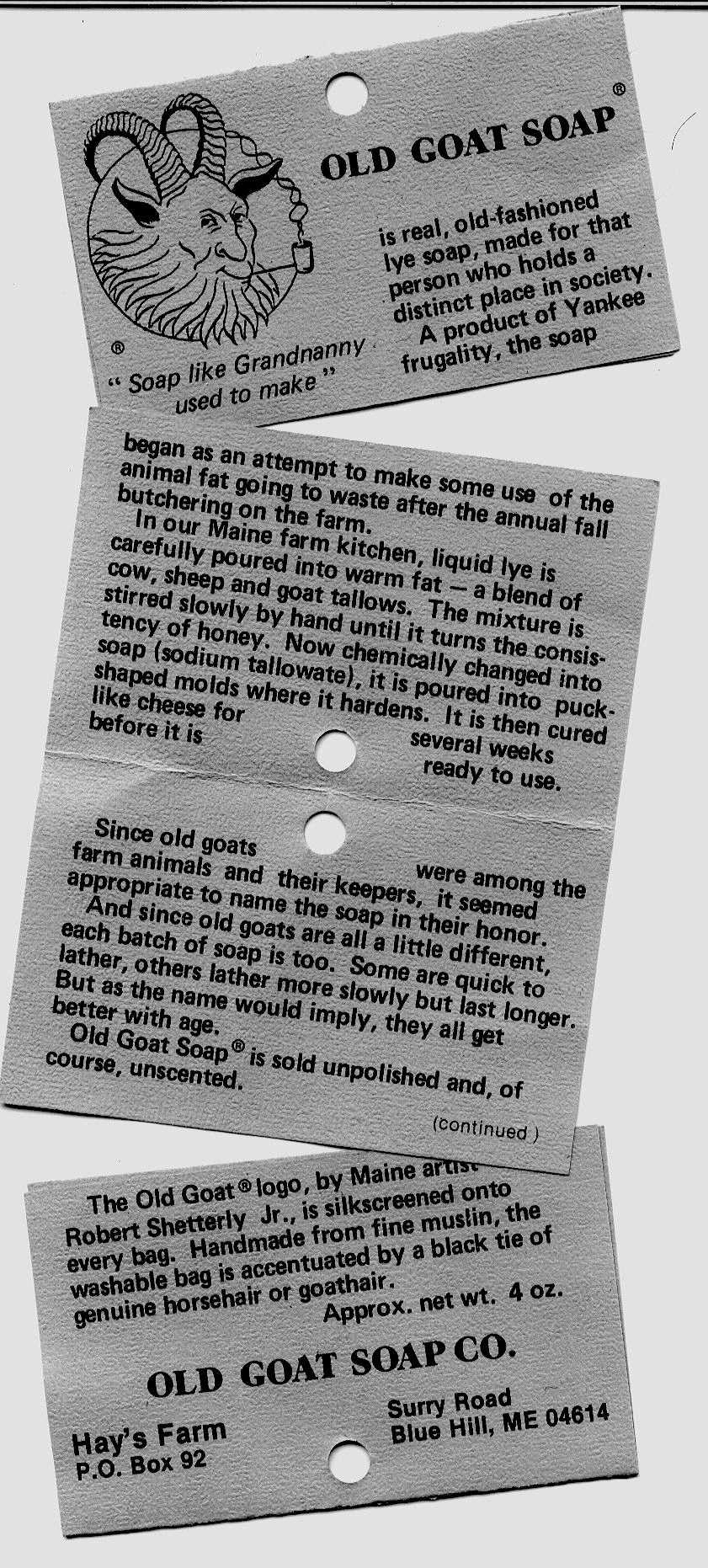

Thus it became known as ``Old Goat Soap.'' I bought muslin by the bolt and made miniature replicas of grain bags to hold it. The bags were silk-screened in a local shop, with a logo designed, for $50, by prominent artist Robert Shetterly, who was then living in nearby Surry. Real horsehair yarn, imported from Italy, was used for the tie at the top. The tag proclaimed, among other things, ``Soap Like Grandnanny Used to Make.'' I even got an official, U.S. government trademark on the thing.

Thus it became known as ``Old Goat Soap.'' I bought muslin by the bolt and made miniature replicas of grain bags to hold it. The bags were silk-screened in a local shop, with a logo designed, for $50, by prominent artist Robert Shetterly, who was then living in nearby Surry. Real horsehair yarn, imported from Italy, was used for the tie at the top. The tag proclaimed, among other things, ``Soap Like Grandnanny Used to Make.'' I even got an official, U.S. government trademark on the thing.

Unfortunately, it was a hit. We could only make about a thousand bars a winter with the fat that we had, and demand was higher. I even got an offer from a promoter with stars in his eyes who asked if I could tool up to make 10,000 bars a month, because he knew they would be a big item in the boutiques in California. I did the math, even looked into buying rendered sheep fat, and figured out it could be done.

And then I stopped. I realized I didn't want to spend any more of my time making Old Goat Soap. I had more important things to do. I didn't know exactly what those were, but Old Goat Soap wasn't among them.

I haven't made a bar for six or seven years. Haven't needed to. I'm out of the farmstand and the sheep business. And I am slowly depleting the limited supply I have in my attic.

But I did put the specially designed Old Goat Soap wooden soapbox, complete with stenciled trademark and logo, to good use one more time. The occasion was the 1994 Democratic Convention in Augusta, where I stood on it so I could be seen over the high lectern when I gave my requisite candidate speech. Despite the cliche, I know of no other candidate in recent years who has actually used a soapbox for a political speech. And even in the old days, I think one would have been hard-pressed to find any of those politicians standing on their soapboxes on street corners who actually owned the trademark on the box.

Heirlooms -- continued (click here)

I was a little hesitant in my new job. In my employment interview, when I tentatively asked just what an editorial assistant did, Westerly bureau chief Norm Warner said he didn't have a clue. The main office had ordered its two southern-most news bureaus to be consolidated, and authorized the new position for which I was applying. He assured me that he would think of something, and hired me on the spot.

I was a little hesitant in my new job. In my employment interview, when I tentatively asked just what an editorial assistant did, Westerly bureau chief Norm Warner said he didn't have a clue. The main office had ordered its two southern-most news bureaus to be consolidated, and authorized the new position for which I was applying. He assured me that he would think of something, and hired me on the spot. So far the desk has survived several moves and has proved more durable than two long-term relationships, including the one in effect at the time of its acquisition.

So far the desk has survived several moves and has proved more durable than two long-term relationships, including the one in effect at the time of its acquisition. The cat, named Lilly, is also a cast-off, rescued from the local pound after I heard rodent scratchings inside the walls of my newly acquired, uninsulated, 100-year-old house in Bangor in early 1996. A week later I found a dead and masticated rat in the middle of the dining room rug. Since then, Lilly has done a fine job keeping the bats out of the attic, although I wish she wouldn't jump on the bed with them in the middle of the night.

The cat, named Lilly, is also a cast-off, rescued from the local pound after I heard rodent scratchings inside the walls of my newly acquired, uninsulated, 100-year-old house in Bangor in early 1996. A week later I found a dead and masticated rat in the middle of the dining room rug. Since then, Lilly has done a fine job keeping the bats out of the attic, although I wish she wouldn't jump on the bed with them in the middle of the night. Two other large slabs were sistered and made into a large dining room table by Keith R. Heavrin, Jr. It remains with him at his home in Harborside, Maine. A third, smaller slab from farther up the tree, is now a coffee table owned by our daughter Rebecca Heavrin.

Two other large slabs were sistered and made into a large dining room table by Keith R. Heavrin, Jr. It remains with him at his home in Harborside, Maine. A third, smaller slab from farther up the tree, is now a coffee table owned by our daughter Rebecca Heavrin. and a smelly oil burner in what passed for the living room. We had heated solely with wood in our homesteading cabin on our 22 acres in Harborside. I was undeterred. The first few winters were unbelievably cold. The house got more comfortable over the years as I pulled down old plaster walls and insulated between the post and beams and full-dimension studs.

and a smelly oil burner in what passed for the living room. We had heated solely with wood in our homesteading cabin on our 22 acres in Harborside. I was undeterred. The first few winters were unbelievably cold. The house got more comfortable over the years as I pulled down old plaster walls and insulated between the post and beams and full-dimension studs. ``Gee, I know some people who restore pianos,'' I said excitedly. ``Can I talk you into trucking that to my house in Blue Hill?''

``Gee, I know some people who restore pianos,'' I said excitedly. ``Can I talk you into trucking that to my house in Blue Hill?''

For the next seven years I grew vegetables, strawberries, raspberries, herbs and flowers. My partner Dennis grew the bigger stuff that could be tended from a tractor, such things as corn, squash, potatoes, rows and rows of carrots.

For the next seven years I grew vegetables, strawberries, raspberries, herbs and flowers. My partner Dennis grew the bigger stuff that could be tended from a tractor, such things as corn, squash, potatoes, rows and rows of carrots.  Thus it became known as ``Old Goat Soap.'' I bought muslin by the bolt and made miniature replicas of grain bags to hold it. The bags were silk-screened in a local shop, with a logo designed, for $50, by prominent artist Robert Shetterly, who was then living in nearby Surry. Real horsehair yarn, imported from Italy, was used for the tie at the top. The tag proclaimed, among other things, ``Soap Like Grandnanny Used to Make.'' I even got an official, U.S. government trademark on the thing.

Thus it became known as ``Old Goat Soap.'' I bought muslin by the bolt and made miniature replicas of grain bags to hold it. The bags were silk-screened in a local shop, with a logo designed, for $50, by prominent artist Robert Shetterly, who was then living in nearby Surry. Real horsehair yarn, imported from Italy, was used for the tie at the top. The tag proclaimed, among other things, ``Soap Like Grandnanny Used to Make.'' I even got an official, U.S. government trademark on the thing.